“We would operate from Trincomalee in what were known as ‘Club Runs’. We would go down with one or two carriers and some cruisers, and we would go and attack Japanese bases in Sumatra in particular ... We really started to learn our job against the Japanese for our eventual part in the British Pacific Fleet.”

“Life aboard the carrier, out in the bay, was infinitely more genial. For one thing, there were no insect pests. But nowhere could one escape the heat. Nor could she provide food in any better shape than the mess ashore, for there was little you could do with powdered egg, powdered milk, powdered potatoes and corned beef that ran from an opened can in a turgid stream of tepid sump oil conveying a few streaks of red meat.”

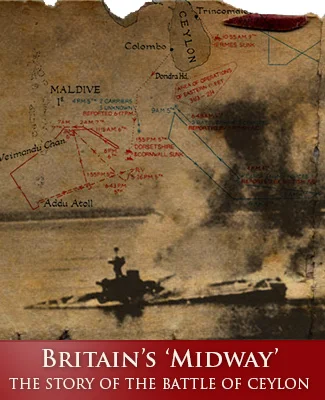

'PIVOT' TO ASIA

Waite Brooks, The British Pacific Fleet in World War II: An Eyewitness Account

The harbour at Trincomalee was vastly different from the naval bases we had been operating from in the past. Its entrance was a passage through the jungle that lead into a large central bay. Slender inlets ran like fingers from this central bay, poking holes in the jungle that ringed the harbour. A huge fleet and its supporting fleet train filled all available harbour space. Battleships, a row of fleet aircraft carriers, several heavy cruisers, a large number of light cruisers, and two destroyer depot ships with lines of destroyers moored about them, occupied most of the central bay and several of the inlets. Two submarine depot ships with submarines clustered along their sides, rows of escort vessels, a motor torpedo boat base with a swarm of motor torpedo boats and motor launches, a floating dry dock, a hospital ship, a repair ship, and fleet oilers were tucked into the remaining inlets and bays. A squadron of Catalina flying-boats bobbed about at their moorings at the head of a small cove...

The shoreline to the north and west was heavy jungle right to the water’s edge. Carved out of this forest to the west was a large oil tank farm and an airfield. To the east, the harbour was separated from the ocean by a relatively narrow, sandy isthmus that ran to a wide, rugged point shaped rather like an animal’s head whose open mouth formed one of the harbour’s many coves. An elaborate boom defence ran from this point westward across the harbour entrance to the other shore. Radar aerials protruded out of the trees on many of the hills, and antiaircraft gun batteries were located around the harbour and on several of the islands in the harbour.

The nature of war would change dramatically for the Royal Navy in 1944. The surrender of Italy freed up much of the Mediterranean, while the remaining surface units of the Kriegsmarine were firmly bottled-up in their Baltic and Norwegian ports.

Great Britain could now begin to focus a meaningful force on what had been its third front – Southern Asia.

The first sign of what would become a major shift in surface forces was the arrival in Ceylon of HMS Illustrious on January 27, 1944, with HMS Unicorn, Queen Elizabeth, Valiant and Renown.

In March, the escort carriers HMS Begum and Shah joined Battler to assist in Indian Ocean convoy duties. HMS Atheling and Ameer would shortly follow.

Aboard HMS Illustrious were the first two FAA Corsair units to put to sea: 1830 and 1837 Squadrons. Both had only just finished training with the machine and had only just begun he process of working-up to operational status.

It was a timely arrival.

Admiralty intelligence initiated Operation SLEUTH on February 20. A possible German blockade runner was believed to be attempting to break out of the Far East on a dash back to Europe. HMS Illustrious, with HMNZS Gambia and destroyers Rotherham and Tjerke Hiddes (Dutch) in company, sailed from Trincomalee on February 22 to attempt an intercept. The force scoured the area south-west of Cocos Island. No trace was found of the supposed raider.

As the new elements of the British Eastern Fleet adapted to Trincomalee, the Japanese initiated a similar ‘pivot’. Five battleships and three fleet carriers moved into Singapore – fleeing the carnage that had been their forward base at Truk in the Caroline Islands.

Was this a sign of pending Japanese forays into the Indian Ocean? Could that mean the Japanese carriers observed to be assembling in and around Singapore - including the armoured Taiho - were about to sortie?

The fight against the Japanese was very different to which the RN was accustomed. Instead of quick offensive strikes under the umbrella of enemy air forces or the hard defensive slog of convoys through contested waters, the war in the Indian and Pacific Oceans was one involving great distances and sustained operations.

The ships – and in particular the carriers – of the fleet had to get up to speed quickly.

The United States was willing to help.

The forward elements of the new core of the British Eastern Fleet, pictured at Trincomalee in February 1944. In the foreground is HMS Unicorn, with the battlecruiser HMS Renown above and HMS Illustrious to the right. The cruiser partially obscured by smoke is either HMS Ceylon or HMNZS Gambia. The fresh arrivals from the Home and Mediterranean fleets have not yet been repainted in Eastern Fleet camouflage.

PRELUDE

With the Japanese Combined Fleet now based in Singapore, the Royal Navy was faced with an urgent situation.

Raids into the Indian Ocean were now much more likely.

Admiral Somerville, Commander-in-Chief of the Eastern Fleet, had held the Indian Ocean with a laughable assembly of cast-offs from the Home and Mediterranean fleet for several years. He knew his now rapidly growing force needed to be trained. Fast.

What followed was one of the rare acts of cooperation between Somerville and the flamboyant Supreme Commander South-East Asia, Lord Mountbatten, who would later have the Admiral removed. Mountbatten's taste in large media teams and big black cars was similar to that of US Admiral Ernest King. Whatever affinity there was between the two produced a surprising boon.

The presence of a US fleet carrier would both bolster the Eastern Fleet’s strength, and provide another opportunity for FAA personnel to learn about the demands of the Pacific war.

Admiral Nimitz complied.

He diverted USS Saratoga – and her air group of 69 Hellcats, Dauntless and Avengers – along with three destroyers.

It was a vital precursor for what was to come.

The Royal Navy was in the process of preparing for operations in the Pacific. The Indian Ocean was being used as a testing ground - and human experiment.

Key ships were undergoing urgent anti-aircraft and accommodation upgrades. Cruisers would have their “X” turrets removed and replaced with Pom Poms or 40mm Bofors mounts. Battleships and destroyers would get extra 20mm guns. All would get the new proximity fused anti-air ammunition.

The fleet carriers would also receive modern aircraft, and have their anti-aircraft radar and armament control systems improved.

A lucky few would get air conditioning.

Admiralty calculations had already determined the need for 74 ships of 19 types to supply necessary mobile oiling, storage, accommodation, distilling – and even entertainment – facilities for the Eastern and Pacific Fleet. Where these would come from was not yet clear.

Then there was the additional lack of suitable destroyers.

The Battle of the Atlantic was still intense. Protecting the arterial supply lines to the Home Islands remained top priority.

But the pressure was begining to ease.

AIR ARM

“We sailed on another ‘Calcutta sweep’ on March 8 hoping, we were told, to draw enemy forces out of Singapore. They chose not to play with us, but the flying was invaluable; and you can’t take the Fleet to sea every day just to give the boys a fly-around! On our first full day at sea, ‘Tiddles’ Brown did a shaky landing and put his port wheel over the side into a gun sponson. He bent the aircraft but he himself was unhurt.”

The Swordfish and Albacore had by now been replaced by the Barracuda II. But the 12 months this hybrid dive-and-torpedo bomber had been in service revealed serious deficiencies.

HMS Victorious had received a complement of Lend/Lease TBF Avengers during her earlier deployment to the Pacific. More had been pressed into service aboard escort carriers in the anti-submarine role.

Comparisons with the US aircraft were not favourable for the Barracuda. But the Royal Navy persisted: The 'Barra' was intended to be more of a multi-role aircraft than the Avenger – specifically in dive bombing. And the Avenger could not carry the superior British 18in Mk XIIB torpedo. Besides, adequate supplies of the US aircraft were not guaranteed.

The Barracuda, however, had long been hobbled by short-sighted political decisions during its much delayed development process. It was designed to operate a new high-pressure-air-cooled inline ‘X’ engine named ‘Boreas’ (nicknamed ‘Exe’). This project was cancelled in 1940 as part of an emergency focus on a handful of fighter and bomber types as a result of the Battle of Britain. As a result, the Barracuda had to fit the less powerful Merlin powerplant.

But the harsh realities of the Indian Ocean would soon result in the Barracuda being taken off RN flight decks. Tropical conditions exacerbated the aircraft’s insufficient engine power, and its effective combat range plummet to just 100 nautical miles.

Urgent action was taken to arm fleet carriers with Avengers at the earliest available opportunity.

The Fleet Air Arm – also unable to get meaningful numbers of the F6F Hellcat due to the immense demand to equip a flood of new US carriers – was fortunate to secure decent stocks of the F4U Corsair. Rejected as unsafe by the USN, the RN found the curved landing approach it had adopted for the long-nosed Seafire also suited this heavy fighter. Even clipping the wingtips to fit the armoured carriers' low hangars had an unexpected benefit: It reduced the Corsair's tendency to 'float' on the landing approach.

Hanson, Norman. Carrier Pilot: One of the greatest pilot’s memoirs of WWII

Just before the change-over was effected, Admiral Mountbatten visited us in harbour and combined a social call on the Captain with an official visit in his capacity as Supreme Commander of the forces in South-East Asia. He was brought to the flight-deck by the after aircraft lift and was immediately introduced to all the heads of departments.

‘Bull’ Cullen, Commanding Officer of one of our Barracuda squadrons, was standing on my right. He shook hands with the great man.

‘So you fly Barracudas, Cullen? And what do you think of them?’

‘Very good aircraft, sir,’ said Cullen, standing rigidly to attention and staring fixedly in the direction of Rangoon.

‘Really?’ said the Admiral. ‘I’ve had other comments. Have you flown better aircraft?’

‘Er, yes, sir. I think I have.

’ ‘Much better aircraft? I’ll tell you why I want to know. I have just left your opposite number down the line there and he tells me they’re bloody awful.’ A pause. ‘Do you really like them?’

‘Er, not exactly, sir. We could have better.’ Poor Cullen wasn’t enjoying this a bit.

‘That’s more like it, Cullen.’ There was another short pause. ‘In fact, I suspect you dislike them just as much as he does.’ Cullen was listening intently. Then the Admiral spoke again, very softly and infinitely kindly. I suppose I was the only outsider to hear. ‘Listen, old chap. What I am here for is to have you tell me precisely what you think. Never try to tell me what you think I might like to hear. There’s a good chap— and the best of luck.’

You’re wasting your time trying to flannel a man of Mountbatten’s calibre.

Corsairs aboard HMS ILLUSTRIOUS wear the SEAC roundel (blue ring surrounding a white circle) used by the British Eastern Fleet.

Mr Thomas Stanton, a civilian engineer who joined ILLUSTRIOUS in December 1943, as Technical Advisory Representative for Chance-Vought Corsairs, chatting to pilot Sub Lieut (A) A W Sutton, of Saskatoon, Canada, after his return from the attack on Surabaya.

The carrier HMS Illustrious was transferred to the Eastern Fleet on January 28. With her were 810 and 847 Squadrons equipped with 12 Barracudas each, and 1830 and 1833 Squadrons with 14 Corsairs each.

Experience with “USS Robin” (HMS Victorious) a year earlier had revealed the need for a much larger flight deck and hangar crew to sustain operations at the Pacific level of intensity. HMS Illustrious, now carrying 54 aircraft through adopting a large deck park, would find herself seriously overcrowded.

Nevertheless, the presence of the maintenance carrier HMS Unicorn relieved some of this strain. The dedicated facilities of her workshops and hangars meant the more complex jobs could be taken off the hands of the fleet carrier.

Unicorn was also a source of reserve aircraft – as well as a ‘spare deck’ with suitable radars to contribute to CAP operations, if needed. She also carried four Swordfish of 818 Squadron as her own for supplementary anti-submarine patrols.

The five new naval air stations in Ceylon and India were rapidly being built up. Some 34 FAA squadrons could be deployed here, ahead of their carriers

OPERATION ‘DIPLOMAT’

“Towards the end of March we were at sea again, trailing our coat in the Indian Ocean. Some strikes were in the offing but without Victorious, whose arrival in China Bay we expected very shortly, we couldn’t tackle the job alone. The great Saratoga, the last big carrier of the US Navy’s old guard, was coming round from Esperitu Santos in New Britain to join us for a time; and we were out to rendezvous with her.”

The US carrier’s arrival was none too soon.

An ominous portent was seen in mid March.

Three Japanese heavy cruisers sortied into the Indian Ocean. Two merchant ships were caught and sunk off the Cocos Islands

On March 19, 1944, the Eastern Fleet – led by HMS Illustrious - sailed to cover the convoys operating between Australia and India.

Distant Cover:

Carrier: HMS Illustrious

Battleships: HMS Queen Elizabeth, Valiant

Battlecruisers: HMS Renown (Flag )

Cruisers: HMS London, Cumberland, Ceylon, HMNZS Gambia

Destroyers: HMAS Napier Norman, Nepal and Quiberon, HMS Quilliam, Pathfinder, Queenborough, Quality and HMNLS Van Galen and Tjerk Hiddes.

At this time, HMS Illustrious was operating with the following air group:

1830 Squadron: 14 Corsair II

1833 Squadron: 14 Corsair II

810 Squadron: 12 Barracuda II

847 Squadron: 9 Barracuda II

Commanded by Rear Admiral C. Moody, the Eastern Fleet failed to find any trace of the Japanese raiders.

Instead, the force used the opportunity to put into practice some of the new skills necessary for future operations against the Japanese: Underway refueling - both of the capital ships and destroyers, and in re provisioning Illustrious' aviation supplies.

The rendezvous with the fleet oilers was a well choreographed affair. The captain of the escorting Dutch cruiser Tromp had ensured all were in line abreast formation and steaming at a steady 10 knots when the fleet arrived. Nevertheless, progress was slow. Oiling took place between March 24 and 26.

Then the force set forth to greet the arriving USN task force southwest of the Cocos Islands.

“She made an impressive sight as she and her three attendant destroyers climbed out of the southern horizon to meet us. They had run into a typhoon whilst crossing the Great Australian Bight and had taken some punishment, but Saratoga’s menace and power were there for all to see.”

From 'Illustrious', by Kenneth Poolman:

As they approached the western edge of Australia, over the distant horizon like a breath of spring came the Americans. Straight for the British Fleet like John Paul Jones came the great carrier Saratoga, queen of the Pacific.

And as she met Illustrious on that bright blue day, history met history face to face, veteran shook hands with veteran. The British ship brought with her Taranto, Salerno, and the Malta Convoys; Saratoga the glory of Guadalcanal and the Solomons, Rabaul and the Gilberts and Marshalls.

Saratoga, CV-3, affectionately known as ‘Sara’ by every matelot in the U.S. Fleet, was a unique ship in many ways. Almost the oldest carrier afloat, and certainly the oldest to be operating as one of a fast carrier task force, she was the biggest aircraft carrier in the world...

At 1145 on March 27, the two forces sighted each other. The US force consisted of:

Task Group 58.5

Carrier: USS Saragtoga

Destroyers: USS Dunlap, Cummings and Fanning.

Aboard Saratoga was the 78 aircraft of Air Group 12:

VF-12 (36 F6F3 Hellcats)

VB-12 (24 SBD-5 Douglas Dauntless)

VT-12 (18 Grumman Avengers)

Saratoga 'manned ship': Lines of sailors in their bright white uniforms lined up in neat order to cheer the British ships. The much more motley RN crews surged to the deck - raising their caps in 'three cheers' as the fleets merged.

Then on to more formal greetings as the allied ships turned back on a course to take them across the Indian Ocean to Ceylon.

Admiral Commanding Aircraft Carriers, British Eastern Fleet, Rear-Admiral Moody, clambered aboard a Barracuda to be flown over to USS Saratoga to meet Captain Cassady and his staff.

The ungainly, preying-mantis appearance of the Barracuda elicited a comment that would go down in aviation mythology: One US lieutenant was reportedly overheard to remark:

'Jesus, the Limeys'll be building airplanes next!'

“Our communications signal crew had been practicing British signals and as the two fleets neared, our crews were preparing to raise British signals but the British beat us to it. They raised American signals. We conceded.”

The crowded, busy flight deck of USS Saratoga.

Saratoga Morning Press: March 30, 1944 (In"U.S.S. Saratoga: CV-3 & CVA/CV-60" By Barbara Stahura):

‘Robbie Jumps Ship’

Lieut. Harold A. Robinson, USN, “Robbie” to his many friends on the ship, has during the course of the past twenty-two months waved thousands of planes aboard and, in the opinion of many, is the ablest landing officer in the U.S. Navy. He has shown quick judgement in emergencies and no doubt averted serious disasters by hair-trigger decisions.

Robbie is bilingual. Beside the ordinary flight deck brand of English, he is a master of the art of expression with paddles, so much so that one pilot complained that he had never before been called so many names as Robbie once signalled to him after a poor attempt at landing.

Things were progressing smoothly, despite a storm on the horizon, as Robbie took his place on the stern at 0645 Tuesday evening. We were in the doldrums – that vacuous condition in which air seems to lose weight, and previously one TBM had to fight its way upward off the waters in launching.

A large and appreciative audience of HMS Cumberland, watching the first landings of American aviators to come within their observation, was matched by an equally large audience on our own flight deck.

The first plane coming in made a sharp turn, lost air speed, and seemed, despite Robbie’s frantic wave-off to be headed for a crash on the flight deck. Robbie had to make a hairtrigger decision and he made it. He had no chance to jump for the landing net which already bears the imprint of his ample frame. He just jumped – and got in what he claims now as a four hour’s flying time between the flight deck and the water.

On this one occasion words failed him.

Immediately the cry “Man Overboard” was sounded and that set in operation several most unusual events. It did not in any way affect the even tenor of Lieut. Robinson’s life. He knew what to do and he was doing it – most vigorously. His shoes and his jacket, which had helped to bring him to the surface, came off. He hastily surveyed the situation, looked at his watch, which was precisely 1905, and about that time some quick-witted seaman had tossed him a life preserver. He swam to it, got in, and then paddled another thirty yards to pick up another life preserver that had been thrown overboard.

On our own bridge the “Man Overboard” signal had been raised at the first cry and the captain of the Cumberland, on our starboard side, had noted it. Many who have been hearing about vaunted British seamanship had never seen it put to the test before. The big cruiser turned toward the Saratoga’s wake instantly, bore down towards the figure floating in the dusk, and a hand-manned whale boat was put over the side, while the cruiser seemed to stop dead immediately.

The USS Fanning had also caught the signal and raced from its position ahead of our ship to the stern. A pall of gloom had descended over the flight deck of the Saratoga and a funeral hush came over all until the signal “Man Safe” was flashed.

Robbie meanwhile was making a study of conditions in the middle of the Indian Ocean. He was still consulting his watch, and timing the various attempts to reach him. The whale boat of the Cumberland came first to his rescue, pulled him aboard, and then, seeing the Fanning bearing down upon it, transferred Lieut Robinson despite his plea about “an oasis in the midst of the Indian Ocean,” a description which a British sailor could not perhaps comprehend…

The return of Lieut Robinson was achieved (the next morning) with pomp and circumstance. The Saratoga has never seen anything like it. A guard of honor, under the direction of Commanders Caldwell and Clifton, stood on the starboard stern. Lieut. Deering handled the paddles and gave Robbie a wave-off as he was pulled over on the lines. And the band struck up “NOBODY KNOWS HOW DRY I AM”. A few officers who had accused Robbie of going to great extremes to secure British hospitality murmured apologies. Everyone was glad to see our landing signal officer aboard again. Robbie too was glad. That is, until someone whispered in his ear, “There are some TBMs in the air.” Then he turned white and sent a boy for his lifejacket.

(Robbie no doubt would have broken his drought in Trincomalee when sampling ample Nelson’s blood at 'sippers' - the usual reward while recounting such a tale to a HMS ships' crews. Then there was the somewhat infamous combined air group party to follow - Ed)

Saratoga's aircraft joined the search for the Japanese raiders - and gave Illustrious its first look at the standards of air operations demanded by the Pacific. Lieutenant Commander Norman Hanson, DSC, RNVR, is quoted in Illustrious by Kenneth Poolman:

"Thursday, March 30th, 1944 ... This afternoon Sara shook us solid with a wonderfully coordinated dive-bombing attack on a towed target, using 18 SBDs and 20 F6Fs. Beautifully executed, followed by a snappy land-on with no prangs!"

Each ship exchanged a batsman and radio operators among the earlier 'diplomatic' exchange via aircraft. If either ship needed to land one of the others aircraft, the appropriate batsman would be given the task of seeing them land-on. Unlike HMS Victorious' visit to the Pacific 12 months earlier, there was simply too little time to train one ship in the other's opposing style.

The carriers conducted joint flying exercises (though not cross-deck flight operations) before the fleet arrived at Trincomalee on April 2.

Also among the early visitors to HMS Illustrious was USN Commander J. C. 'Jumping Joe' Clifton, commander of USS Saratoga's fighter squadron. He, and several of his pilots, were well known to many of the Fleet Air Arm Corsair pilots: They had been among the instructors at Miami Fighter School several years earlier. Others knew each other from the USS Saratoga, HMS Victorious joint operation a year earlier.

But the two carriers had very little time to work up together. Admiral King had asked the Eastern Fleet to attack the Andaman-Nicobar Islands to draw Japanese forces away from planned landings in Dutch New Guinea. The exact date, however, had not been revealed.

They weren't the only ships under pressure: The Free French battleship Richelieu had arrived in Trincomalee from the Mediterranean on the 9th. The escort carrier HMS Atheling was also a fresh sight in the harbor, having arrived just a week earlier.

In just three weeks, this fledgling force had to be a fully coordinated fighting unit.

HMS ILLUSTRIOUS and USS SARATOGA in Trincomalee.

“I dunno ... but it’s bloody funny seein’ them gobs gettin’ pi-ackered on Nelson’s blood. I can see the old bastard revolvin in ‘is grave!”

SARATOGA

Anglo-American relations took a significant upswing during the fortnight at Trincomalee. USN aircrew found the 'wet' wardroom of HMS Illustrious highly generous. In return, FAA pilots found their laundry being cleaned by Saratoga's much superior equipment - and thick dollops of ice cream landing on their plates.

But the reality of war was never far away. The fortnight was crammed with as much joint flight training as circumstances allowed.

With the training over and time almost up, the two carriers put to sea on April 13 for a combined exercise.

It was a shambles.

The breeze was light. Then there was a lack of understanding of each-other's forming up procedures - and Illustrious' poorly practiced intensive launch technique.

USS Saratoga's fighter commander, Commander Dose, is quoted in Poolman's Illustrious:

Due solely, I think, to a lack of any pre-flight joint briefing, it took us an hour and fifty minutes to accomplish even a semblance of a rendezvous, and by that time the planes were so low on fuel that we could do nothing but return to the ships and land.

FAA and USN aviators mingle in HMS ILLUSTRIOUS's wardroom.

Hanson, Norman. Carrier Pilot: One of the greatest pilot’s memoirs of WWII

We saw quite a lot of each other in Trincomalee. Some of them had been instructors during my time at Miami and it was good to see old friends. One such was Commander Joe Clifton, the Air Group Commander. ‘Jumping Joe’ was one of the great characters in my life— and in many others. He was an average-height, thick-set, tough-looking guy, as hard as they come, who had played football for the US Navy— and in America that speaks volumes. He had taught me air-gunnery at Miami. He talked loudly and interminably with only short pauses to allow the intake of breath and smoke from a large cigar, without which he was never to be seen. He was no respecter of persons and it would be a gross understatement to say that he didn’t suffer fools gladly.

The forthright US squadron commander took matters into his own hands. 'Jumpin Joe' Clifton immediately convened a conference aboard HMS Illustrious. Poolman again:

When Jumping Joe arrived he jumped, big cigar and all, straight up to Admiral Moody's territory on the flag bridge. This was hardly accepted British (or American) procedure, but it was typical of Joe, who believed above all in getting things done.

He then held a meeting, as senior aviator, of all the British pilots, at which he shouted clearly and in precise detail the techniques which all the British and American pilots were hence-forth to use in their joint operations.

The meeting was very beneficial. Ideals flowed freely, mostly from behind Jumping Joe's cigar, and the next time they all took off they were able to get together in little over 25 minutes, 'leaving us', as Commander Dose said, 'the long legs necessary for a strike'.

A dawn exercise was scheduled for the next day, April 14. There was no wind. But an optimistic 'puff' saw Illustrious attempt a launch: Only the Wing Leader - popular ace 'Dickie' Cork of Operation Pedestal fame - was able to get airborne. Just.

Eventually the exercise was aborted and Cork ordered to a China Bay FAA airfield. He was killed when landing his Corsair in the gloom - slamming head-on into another Corsair attempting to get airborne. It was an accident that generated a scandal within the FAA that lasts to this day.

Regardless: HMS Illustrious and USS Saratoga had to be ready for a mission in just five days time.

Hanson, Norman. Carrier Pilot: One of the greatest pilot’s memoirs of WWII

I was a long time getting over that one. Silently, I swore like a trooper to think that someone like Dicky, who had already gone through hell and high water, should throw his life away so contemptuously. He deserved a better fate.

Sad, yes. But they would both have been proud and happy to see the full Saratoga air group lined up with our own as a guard of honour as we slow-marched them to their final landing.

“My first sight of enemy territory was of a luscious green island, basking in the early morning sunshine. It was all so very beautiful that when red flashes burst from the deep, verdant green, I felt considerably put out. Good God! It’s enemy fire! Why I was surprised I can’t imagine. I can only suppose that I was appalled that some vandal should set fire to Paradise.”

OPERATION ‘COCKPIT’

A Japanese naval base at Sabang on the northern tip of Sumatra was designated as the target of the Eastern Fleet’s diversionary raid. It had been established to guard the northern entrance to the Straits of Malacca and the approach to Singapore.

Intel on the facility was poor.

Admiral Somerville took a risk: He felt reconnaissance missions to the area would alert the Japanese to the impending attack. They would make do with what they had.

The intention was to conduct a shore bombardment from heavy naval units combined with airstrikes from the two carriers. At the last moment the bombardment was deemed too risky: The attack would be from the air only.

At 11.02 on April 16, 1944, the Eastern Fleet sortied with the following British, United States, French, Dutch, New Zealand and Australian units. It was the first major operation in two years. In the words of Admiral Somerville, the Eastern Fleet “was back in business again”.

Task Force 69: Admiral Somerville

Battleships: HMS Queen Elizabeth (flag Admiral Somerville), Valiant and the French Richelieu

Cruisers: HMS Newcastle, Nigeria, HMNLS Tromp

Destroyers: HMAS Napier, Nizam, Nepal, Quiberon, HMS Rotherham, Racehorse, Petard and Penn, HMNLS Van Galen

Task Force 70: Vice-Admiral A. J. Power

Carriers: HMS Illustrious (Rear-Admiral Moody), USS Saratoga

Battlecruiser: HMS Renown (Vice-Admiral Power)

Cruisers: HMS London, HMNZS Gambia

Destroyers: HMS Quilliam, Queenborough, Quadrant, USS Dunlap, Cummings, Fanning

ASR Submarine: HMS Tactician

TF70 arrived at its flying-off position some 180 miles south west of Sabang, Sumatra, at 05.30, April 19, 1944. The morning brought with it low cloud and light winds – forcing the carriers to operate at high speed to get the heavily burdened aircraft off their decks.

HMS Illustrious launched a strike of 17 Barracudas carrying two 500lbs and two 250lbs each. This was lighter than the aircraft’s maximum capacity in order to provide a better combat radius. They were escorted by 13 FAA Corsairs.

USS Saratoga flew off 11 Avengers, four hefting a 2000lbs bomb each with the remainder carrying four 500lbs bombs. These were supported by 18 Dauntless dive bombers, each carrying a single 1000lbs bomb. Escort was provided by 16 F6F Hellcats while another eight were sent to strafe Lho Nga airfield.

Together, HMS Illustrious and USS Saratoga operated four Corsairs and eight Hellcats as Combat Air Patrol.

USS Saratoga’s strike arrived on target at 06.57, with HMS Illustrious’ wing coming from a different direction just one minute later.

A Fairey Barracuda leaves huge fires, showing the success of the attack, as it returns from the raid.

Surprise was complete.

Anti-aircraft batteries did not open fire until well after the first bombs had fallen.

The Japanese fighter aircraft were caught on the ground. Some 21 were believed destroyed at Sabang airfield and four at another nearby field inland. Three more which made it into the air were shot down.

In all 12 American aircraft were hit by ground fire. The only loss was a US Hellcat which was forced to ditch in sight of Japanese gun emplacements. It was flown by Lieutenant (jg) Dale 'Klondike' Klahn, the wingman of VF-12's commanding officer - 'Jumpin Joe' Clifton - with whom he'd flown more than 500 hours. Commander Clifton was heard to shout over the radio: "He must be saved".

The rescue submarine HMS Tactician complied, pulling the pilot from the water while under fire.

Hanson, Norman. Carrier Pilot: One of the greatest pilot’s memoirs of WWII

We dived down ahead of the Barracudas, firing enthusiastically at warehouses and quays and suddenly found ourselves at the far end of the harbour, unscathed. We were still green and hadn’t yet learned about targets of opportunity. So we milled around like a lot of schoolgirls and left it to the Barracudas, who made a splendid attack on the harbour and oil installations. The Corsair boys returned to China Bay with a feeling of anticlimax. We had been to the enemy and had found no opportunity to cover ourselves with glory. But we would learn.

Sabang burns in the background as HMS Tactician, indicated by the arrow right, moves up - under fire - to pull a downed US Hellcat pilot out of the water.

Commander Dose, USN, in 'Illustrious', by Kenneth Poolman: :

One of our fighter pilots, Jumping Joe's wingman, was shot up by AA over the field, but managed to limp on - on fire - about three miles to sea where he baled out and manned his rubber life raft. I remained with twelve fighters, three divisions, to cover the downed pilot and the sub, while the groups departed and returned to the task force.

The British submarine was stationed as rescue picket about fifteen miles north. The submarine, incidentally, had stayed on the surface during the entire attack watching the whole show.

She proceeded immediately in the direction of the downed pilot. It took almost an hour to reach him. As the submarine approached a position about three miles from the pilot, his path took him fairly close and parallel to the shore line. At this point we observed large splashes within a submarine's length of the sub. The division of four which I had spotted above the airfield at 12,000 feet recognised the splashes as fire from the shore battery, spotted the battery, and strafed it into silence.

The submarine, meanwhile, still surfaced, deviated not one degree from its course. It proceeded deliberately and calmly the remainder of the distance, picked up our pilot, and headed to sea and submerged.

We were impressed with the courage and seamanship of the commander and crew of that submarine. They could have anything we owned.

The harbour and airfield were extensively damaged. Three out of four of the major oil tanks were set on fire. The minelayer Hatsutaka and the transports Kunitsu Maru and Haruno Maru were sunk.

As Admiral Somerville put it, the Japanese were ‘caught with their kimonos up’.

Nevertheless, the planned follow-up bombardment by battleships and cruisers was cancelled in part due to concerns that the 'hornet's nest' had been stirred.

After the USN and FAA strike groups were recovered, a force of G4M Japanese torpedo bombers were detected approaching the fleet late in the morning. The Hellcats of the CAP dealt with them swiftly, shooting three down some 20 miles out.

A generally forgotten follow-up attack justified Admiral Somerville's caution: A larger Japanese torpedo bomber attack developed at dusk.

The Japanese managed to penetrate the CAP due to the low-light and heavy cloud. The fleet had to defend itself.

It did so effectively.

The flak barrage accounted for six Kate torpedo aircraft. The carrier "goalkeeper" (point-defence ship), HMS Renown, reported firing 700 rounds of 4.5in shells within 30 minutes.

No ships were damaged.

Bill Kennelly is quoted in Battle-Cruiser Renown, by Peter Smith:

‘Our radar detected what was thought to be a reprisal attack by Jap aircraft. We put up a terrific barrage by pom-pom and AA guns, but it was through heavy cloud and in all that time we never sighted the aircraft at all.’

The drama was also intense aboard the heavy cruiser HMS London. Seaman Gunner John Reekie, who was manning an Oerlikon 20mm cannon during the attack, is quoted in HMS London, by Iain Ballantyne:

It was between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m. and we could hear the Japanese aircraft coming at us and they must have dropped their torpedoes a fair bit out. I saw the phosphorescent wake of one of them coming straight at us. The 4-inch guns opened up on that bearing… blinding and deafening me with their smoke and flame as the London turned sharply. The Saratoga, which was to starboard also turned to starboard pretty sharply. If the London had not turned I am sure it would have hit her right in the stern.

Carrier Air Group 12 (CVG-12)'s official History (USN Air 1207 October 1945) reads:

34. During the day and night several Nakajima B5N Kate torpedo bombers were shot down either by the combat air patrols or anti-aircraft fire. Although many aircraft had been shot down within sight of the ship by her protective aircraft since the war began, it was the first time the Saratoga’s crew had directly fired at enemy raiders.

Operation ‘Cockpit’, while successful, was not spectacularly so.

The Royal Navy was made aware of several key deficiencies.

One was the need to place tactical command of the fleet to the Rear Admiral Aircraft Carriers during flying operations.

HMS Illustrious had moved out of the task force with a light escort of destroyers in an effort to generate enough over-deck wind to launch the lumbering Barracudas.

This had left her dangerously exposed.

Under the advice of the Americans, this would change: The whole fleet would in future manoeuvre in concert with the carriers – forming a constant, close defensive ring.

Then new orders arrived from the United States:

USS Saratoga had given the FAA the wake-up call Admiral Somerville had sought. But every effort had to be made to capitalise upon the Pacific veteran’s experience.

It was resolved to combine Saratoga’s return to Australia and then Pearl Harbor with a strike on a significant aviation fuel facility in Java.

Sabang would become a target of the Eastern Fleet again on July 25. Admiral Somerville's battleships bombarded the harbor facilities as HMS Illustrious' aircraft suppressed operations from the airfields.

Somerville wrote afterwards to Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham:

"The party did everyone a world of good and especially some of the big ships who had not a chance to fire their main armaments in action for quite a while....I am sure that you would have liked to see the Inshore Squadron going into the harbour led by Dick Onslow, as it was a most inspiring sight;he used rather a broader line of bearing than I would have expected,and his tail leaning up against the shell bursts on the targets under fire on the East side of the harbour......"

“Before we sailed from Ceylon on our next operation together, Saratoga and ourselves paid a short visit to Colombo, fetching up there at the end of another exercise. Saratoga went to a lot of trouble to stage the party to end all parties and invited our C-in-C, Admiral Sir James Somerville, and other Fleet officers, and our own air group, partly to repay our hospitality in entertaining them aboard Illustrious in China Bay. (This in itself had proved to be an alcoholic feast of Olympian proportions!)”

OPERATION ‘TRANSOM’

US Navy C-in-C Admiral King wanted Saratoga home to refit ahead of anticipated strikes against Japan.

But he saw Saratoga's return trip as an opportunity to employ the British Eastern Fleet in one more task: He wanted the Japanese base at Surabaya, Java, to be attacked.

Surabaya was the centre of Japanese anti-submarine operations for the region. And a major oil facility was nearby, at Wonokromo.

Again, Admiral Somerville saw this as an opportunity to practice skills needed for the future.

It was a difficult target: Deep within enemy territory on the other side of Java island. Aircraft had to fly 180 miles - partly over mountainous terrain - to reach the target.

As a result, it was outside the effective range of the Barracuda. Two FAA Avenger squadrons – 832 and 845 – were seconded from their Escort Carriers in Trincomalee to provide the necessary reach.

With 18 TBF Avengers between them, these took the place of the 21 Barracudas of 810 and 847 Squadrons aboard Illustrious.

It was also to be the most distant strike so far attempted by the Eastern Fleet: It was actually closer to Australia than Ceylon.

At-sea refueling was to be a necessary function - especially given the short range of RN destroyers.

The operation's planning made another Royal Navy weakness painfully evident. Most of its modern fast tankers had been lost in the desperate battles of the Mediterranean and North Atlantic. Too few remained to keep a large Task Force “fueled, fed and in fighting condition” at sea.

Refueling of heavier units would therefore have to take place at Exmouth Gulf, Western Australia.

Once again, the Eastern Fleet was split. This time as three task forces.

Task Force 65:

Battleships: HMS Queen Elizabeth (Admiral Somerville), Valiant and the French Richelieu

Battlecruiser: HMS Renown (Vice-Admiral Power)

Cruisers: HMS Kenya, HMNLS Tromp

Destroyers: HMAS Napier, Nepal, Quiberon, HMS Quality, Quickmatch, Rotherham, Racehorse, HMNLS Van Galen

Task Force 66:

Carriers: HMS Illustrious (Rear-Admiral Moody), USS Saratoga

Cruisers: HMS Ceylon, HMNZS Gambia

Destroyers: HMS Quilliam, Queenborough, Quadrant, USS Dunlap, Cummings, Fanning

Task Force 67:

RFA Tankers: Eaglesdale, Easedale, Echodale, Arndale, Appleleaf, Pearleaf

Distiller: Bacchus

Cruisers: HMS London, Suffolk, HMAS Adelaide

The main combat units set sail from Trincomalee on May 6. The fleet sailed at a leisurely 18 knots by day to reduce giveaway funnel smoke, ramping things up again at night to 20 knots. It also kept a healthy 600 mile margin between it and any known Japanese airfield to minimise the risk of detection.

The first refueling of destroyers was conducted on May 10 – in heavy seas – from the battleships and carriers. The fuel-line astern method proved slow going. The Royal Navy was at this point nowhere near as proficient at underway replenishment as their US counterparts.

It’s something the officers of USS Saratoga noted – and relayed back to Admiral King.

The main fleet met the pre-positioned tanker force in the sheltered anchorage of Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia on May 15.

As the fleet closed on the target, HMS Renown, London and Suffolk took up station with the carriers – operating with Task Force 66. The battlecruiser in particular was seen as an important boost to the group’s anti-aircraft defences.

Task Force 66 arrived at its launch position about 180 miles south of Java at 04.30 on May 17.

The weather was fine with a few scattered clouds and a light southeasterly wind.

Two strike forces formed up.

Force A was to hit the Wonokromo oil refinery facilities. Nine FAA Avengers were to hit the Braat Engineering Works with their loads of four 500lbs General Purpose Bombs. Twelve of Saratoga’s Dauntless were ordered to attack the oil tanks. Escort was eight FAA Corsairs.

Force B was to bomb the Surabaya harbour. Six FAA Avengers were directed towards the naval workshops, while another three were to attack a floating dock. Once again, the bombers would carry four 500lbs bombs each. Eight Corsairs formed the designated close escort. Accompanying this force was to be six of Saratoga’s Dauntless dive bombers, each hefting a 1000lbs bomb. Their job was to attack a cruiser that had been reported in the harbor, as well as floating docks and harbor facilities. Twelve of Saratoga’s Avengers were tasked with attacking merchant shipping and commercial harbor facilities. Close escort was 12 Hellcats.

Once again, the formations arrived in a timely manner and surprise was complete.

No Japanese aircraft were encountered, and anti-aircraft fire was ineffectual. Bombs were dropped on the harbor, warehouses and oil facility. All were seen to be burning fiercely. At the nearby Japanese airfields, 12 aircraft were caught on the ground.

The FAA's raid on the Wonokromo oil refinery was effective, leaving it completely burnt-out. One ship was sunk in the docks and the harbour facilities hit.

The raid was deemed a qualified success: Carrier Air Group 12 (CVG-12)'s official History (USN Air 1207 October 1945) reports:

Ten per cent of the Japanese high octane gasoline supply was destroyed in one hour. British planes sank transport Shinrei Maru while the Saratoga’s damage Patrol Boat No.36, auxiliary submarine chasers Cha 107 and Cha 108, the cargo ships Ch_ka Maru and Tencho Maru, and the tanker Y_sei Maru.

One Avenger, from Saratoga, was shot down. The crew was observed to have entered a life raft, but was never seen again.

Both Task Force 65 and 66 withdrew together at 08.50.

The operation proved to be another another harsh lesson in Pacific warfare for the FAA and RN.

The British force commander (Somerville) was not aboard a carrier. He was in a more traditional flagship – the battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth. For this reason he was not quickly appraised of the success – or otherwise – of the air operations.

Lieutenant Commander Norman Hanson, DSC, RNVR, is quoted in 'Illustrious', by Kenneth Poolman:

0100 hours. Haven't had a wink of sleep yet, just flying round the cabin doing bloody deck landings on the pillow.

'D'ye hear there! The fleet will be going into action at 0700 hours this morning. Close up for action stations at 0600!'

Try to sleep once more, without much success.

Shaken at 0500. Dress, clumsily and cursing - shift, flying overalls and gym shoes. Up to the wardroom where everybody toys with breakfast. (The stewards know better than to put anything decent on today.)

Back to the cabin to collect mae west and helmet. Up to the island and into the ready room to await the order. Perhaps it won't come this morning. Perhaps the show's off.

Suddnely, the blowers roar:

'Pilots, man your aircraft!'

All the aircraft have been ranged the night before in order of take-off, fighters first, then bombers. Romp off down the flight deck and climb in. Two air merchants jump on to the wing and help to fix the straps. One of them says:

'Hit 'em sir!'

Sit there, frightened as hell.

'Corsairs start up!' from Wings on the bridge.

Put the mag switch and fuel pump on. Put the booster pump on, hold it with one finger and press the starter with the other.

Run the engine up with a roar to nine hundred revs and leave it there until everything is warmed through. The racked of sixteen Corsairs all doing the same is deafening.

'Avengers start up!'

The noise is so great that the order has to be relayed to the Avenger boys by the mechanics.

Then comes the worst moment of all.

Suddenly, there's the long, heavy noise of the aircraft rising up in front - the ship is turning into wind. You're for it now!

It's a long way home and you can't get out and walk. You shouldn't have joined!

Everything begins to shudder as the ship works up to the twenty-seven knots necessary to get enough wind over the deck - the wind is a whisper in the Indian Ocean, and the ship has to make it all herself today.

The deck is spotted to the last inch, there is no room for mistakes. Musn't unlock the tail wheel too soon, or I might run into another prop.

Right. Out we go. Taxi into position for the take-off, spread the wings and lock them properly as Johnny gives the signal, not forgetting to give him the thumbs-up when you've done it. (That's a new rule brought in after poor old Monty bought it.)

Lower flaps to maximum hard right rudder.

There's Bats 'winding me up' now. Open the engine to maximum and hold the brakes on.

A nod and Bats waves me up the deck.

Away you go laughing. Roar down the deck, past the bridge up to the bows and off.

Once off the deck all one's worries cease. It's a beautiful morning and I'm flying and that's all there is to it.

Bank violently to starboard once clear of the deck and avoid flinging propwash back at the other aircraft behind.

The Wing Leader flies ahead of the ship for about a mile, pulls up his wheels and flaps and does a slow turn to port. Follow behind him downward out on the port side towards the joining up area astern of the ship.

Circle around there for a while, watching the others take off, then join up with the Americans.

And here we are, the whole strike, Hellcats, Corsairs, Dauntlesses, Avengers, the whole of our 'big blue team', roaring steadily through the bright sky together, wing and tail.

I look round and suddenly realise that life is a short thing, that I am lucky to have moments like this. You'll be luckier still if you live to remember your beautiful thoughts...

There's Jumping Joe out ahead of us all. And there's Rowebotham, leading the American Avengers. He's a descendent of Red Indian chiefs, as tough as ironwood, a great pilot.

'Strike leader to all aircraft. Setting course. Out.'

Everybody starts scrambling for height as fast as they can. It's a bloody uncomfortable job, climbing with the slow bombers, hanging on the prop at 130 knots, doing a very wide weave to keep down to their speed.

Okay, try and settle down now, enjoy the ride. We drone on over the glittering sea of Java.

There's the green of the coast now! How pretty it loos - real blue lagoon stuff.

God, it's enemy coast! All right, no more natter over the R/T. Keep your head on ball bearings from now on. Listen to the engine a bit more acutely too. There's only one - got to look after it.

Good Lord! DOwn below is a gently smoking volcano! Suddenly, with a shock - there's the sea! We're there!

Weave to and fro, looking into the faces of the bomber pilots - only a hundred feet away, some of them, and all going like dingbats now.

The signal from Bomber Leader. Go into echelon, with half the fighters on one side of the bombers, half on the other.

Watch Hathron's SBD.

There he goes now - rolling over on his back. That means us. Roll over and go down with him.

Down ... down ... down ... pull out now ... aah!

There's Jim Hathorn pulling out.

Oh bloody good! He's put it slap bang into the middle of those cracker retorts!

The R/T crackles. Jim's voice -

'Don't waste your bombs, it's finished'

Okay, that's one lot. Now - up the road and see our chaps in. There they are.

Now we're up with them. Down they go.

Oh lovely shooting! They're dropping them right through the letter-box with eleven and a half second fuses. Right on top of the engine works, not a single one on the road. There's a POW camp on the other side of the road from the target. I bet the lads in there are getting a good view. A beautiful bit of bombing.

Now it's time to take the boys out to sea and pick up the Dauntlesses again. Down low over the water then, till it flashes past like a big steel plate. That's what it would feel like too if you ditched at this speed, so watch out for Nips.

Hello, look at that big bastard steaming in across the bay for Surabaya! Oh, we'll have to have a crack at you chum! Down we go and give him a bellyful of armour piercing and incendiary.

Not bad shooting. I plastered the bridge real good and proper, anyway.

Christ! Where did that lot come from! ... It's tracer from the Hellcats beating up the harbour.

There's Jim and the SBDs. Good show.

Back home now with the bombers at 8000ft. Anybody missing? Seem to be one or two gaps. My lot's all right, anyway.

“Please extend my congratulations to Commander-in-Chief, Eastern Fleet, and his command on so satisfactorily completing a mission, which inflicted important damage on the enemy.”

Again, the Americans demonstrated the level of responsiveness necessary for a successful attack at this scale.

One of Saratoga’s aircraft dropped photo-reconnaissance prints taken by a (PR)Hellcat immediately after the raid to HMS Queen Elizabeth (Somerville) and HMS Renown (Power).

These revealed many targets in the harbor had escaped unscathed – including the submarines.

A follow-up attack was warranted.

The British commanders – not expecting such a high-quality assessment so quickly – found themselves wrong footed. It was too late to turn back.

Admiral Somerville recognised the lesson: He immediatley set in motion a chain of events that would eventually see a Hellcat PR unit delivered to the Eastern Fleet in October. Some of these aircraft would deploy with HMS Indomitable as part of the British Pacific Fleet.

USS Saratoga and her three accompanying destroyers separated from the Eastern Fleet as the force withdrew on May 18.

She was no longer needed. The armoured carriers HMS Victorious and Indomitable had by now arrived at Trincomalee.

Thus ended what Admiral Somerville called ‘a profitable and very happy association of Task Group 58.5 with the Eastern Fleet’.

“‘Sara’ and her destroyers formed in column. One by one past her port side steamed the entire array of Allied ships with which she had been associated for something over seven weeks. The column reached from horizon to horizon. As each man-of-war passed close abeam with such ‘Auld Lang Syne’ wafting across the interval and signal hoists spelling in the breeze their messages of goodwill, men and officers gave the traditional British ‘three cheers’. We returned these honours in kind and in a Navy not given to cheering there were some raw throats that night”

FAREWELL

Determined not to be out-done by USS Saratoga's smart welcome less than two months earlier, the allied units of the British Eastern Fleet had planned to give her a send-off to remember.

Crews lined the decks. Signal flags were streamed. Messages were composed and sent by lamp.

It was a spectacular sight on slight seas under the blue skies.

The Eastern fleet was arrayed in line-ahead; a formation which stretched form horizon to horizon.

One by one the ships - large and small - cheered the US carrier and her attendant destroyers.

The Eastern Fleet refuelled at Exmouth Gulf on the 19th before returning to Trincomalee harbour on May 27 after a round-trip of some 7000 miles.

To C-in-C, E. F. from C.T.G.58.5:

On our departure, may I ask that you express to every officer and rating of your fleet the best wishes of every officer and rating of Task Group 58.5. Not only has it been a pleasure to serve with you but it has been an honour. We leave you in the highest regard and we know that great things will be accomplished by you. All of us wish all of you Good Luck, Good Hunting and may God be with each of you in your future undertakings wherever and whatever they may be.

To C. T. G.58.5 from C-in-C E.F.:

Your message, which will be promulgated to my fleet, is very much appreciated. You have done grand work with us and we view your departure with great regret. We hope that good fortune will make us fleet mates again in the future. Good Luck and God bless you.

To C-in-C, E. F. from C.T.G.58.5:

Many, many thanks for the splendid send-off. We shall always remember it.

“... sailing back to refuel at Exmouth Gulf, we said farewell to Saratoga. We had enjoyed their refreshing company, both ashore and afloat. We had admired their efficiency and single-mindedness. We had made new friendships and had cemented old ones. It was a sad moment as she steamed slowly past, acknowledging our salute, our full-blooded cheers and our farewell to good and brave friends. Then she and her destroyers slid into the murk of the gathering darkness to the south. Godspeed!”

AFTERMATH

The Surabaya operation was ultimately to drive another barb into the relationship of Lord Mountbatten and Admiral Somerville. The self-aggrandising appointee of Churchil claimed in the media that the attacks on Sabang and Surabaya was by “ships of Mountbatten’s Command”.

HMS Illustrious was, for the time being, the sole fleet carrier in the Indian Ocean. She would attempt an offensive sweep in the Bay of Bengal between June 10 and 13 with the support of the escort carrier HMS Atheling. But, for a raid on Port Blair in the Andaman Islands on June 19, the fleet carrier operated alone.

But her operational tempo was by now significantly improved. On July 21, HMS Illustrious had 53 out of her expanded air group of 57 Corsairs and Barracudas in the air at the same time. The risk, however, was high: Recovering this force still took more than an hour. A deck accident could have resulted in much of her wing being forced to ditch. There was no suitable ‘spare deck’ available.

But help was now at hand.

HMS Victorious and HMS Indomitable had joined the fleet.

Admiral Somerville’s last operation as commander of the Eastern Fleet was to take HMS Illustrious, Victorious and the fleet’s big guns on a successful bombardment of Sabang on July 25. The carriers landed most of their Barracudas in order to take on extra Corsairs for a more in-depth CAP.

A half-hearted counter-attack by Japanese forces resulted in the Corsairs of Illustrious downing three Ki-43 ‘Oscars’ and a Ki-21 ‘Sally’. A Corsair pilot from Victorious downed a fourth ‘Oscar’.

Admiral Somerville signaled: “I consider this has been a very good party in that all units taking part acquitted themselves most creditably… It was nice work, pretty to see, and better still to have taken part in.”

As Admiral Somerville departed – vanquished by the relentlessly ambitious Mountbatten - so too, for a short time, did Illustrious.

The tired old veteran left Victorious and Indomitable behind for a quick refit in South Africa. It was her first in more than a year. It would be her last before the end of the war.