“The Wildcat was a great asset to the Fleet Air Arm, bringing it to nearly the level of the fighter opposition. It was also an aircraft specifically designed for modern carrier operations, thereby setting new standards for British designers in the field. The Wildcat was a potent fighter, with splendid maneuverability, good performance, heavy firepower, and excellent range and endurance. On top of this, it was a superb deck-landing aircraft.”

Operational Notes

Endurance

The Martlet's strong loiter ability was constrained by other factors: Namely, human endurance. Fleet Air Arm Combat Air Patrols in the Mediterranean in the early years tended to be limited to about two hours for both the Martlet and the Fulmar - not through any deficiency in the machines, but because of pilot fatigue and the need for extensive reserves. The constant submarine, air and surface threat of that unique theatre would result in last-second manoeuvres by the fleet - forcing the carrier to abort landing operations until the "all clear" was given.

This could often be 20 minutes or more.

'Hank' Adlam learnt this the heard way:

The patrols were limited to the two-hour duration to retain sufficient fuel at the end of the patrol in case combat action became necessary; my experience of some six months earlier when I had been forced to ditch out of fuel, proved the point.

Deck Landing

“The Wildcat was not all that easy to deck land because its undercarriage, although very strong, was narrow. But despite that factor, it was probably safer if not easier to land on the deck compared with most other fighter aircraft. Moreover, provided the pilot had already manually wound his undercarriage right up, it was reasonably safe to ditch, in so far as the word ‘safe’ can be applied to any ditching.”

Eric 'Winkle' Brown, who would later find the Seafire no problem when it came to deck landings, expressed his opinion of the Martlet's deck landing qualities in his book, 'Wings of the Navy':

I will always maintain that the Martlet had the best landing characteristics of any naval aircraft that I flew… For this necessarily hazardous undertaking, the Martlet was superlative. It offered good forward vision, excellent slow flying characteristics, a robust undercarriage fully capable of absorbing the most punishing vertical velocities and an intelligently positioned arrester hook that could convert a shaky approach into a safe arrival.

“The Wildcat and the Swordfish made a great team together, both of them being ideal for their purpose and able to operate from the deck of small Carriers in the worst weather and sea conditions. Incidentally the author cannot forbear to write that the Wildcat, which he flew operationally for more than two years, was his favourite aircraft of all.”

Combat Comparisons

Adlam described in his book a personal test flight between himself, in a Wildcat, and a friend, in a Seafire. Both were serving aboard HMS Illustrious in 1943 and were undergoing working-up exercises in Scotland.

The unscientific comparison involved a race and a mock dogfight. Nor is the model of the Martlet recorded, though he lists the Seafire as being a "IIC":

For the race, we flew alongside and level at a steady 130 knots and then, at a signal , we both opened the throttles wide. As expected the Seafire was faster and gradually moved ahead but not all that swiftly. We reckoned and agreed afterwards that the Seafire was no more than 7 or 9 knots faster than the Wildcat.

The combat, Adlam records, was something more of an eye-opener:

For the dog-fight, my Wildcat and I were at a disadvantage because Bruce was an exceptional pilot and always had been even while training, whereas I was never in that category. It was interesting to find that the Seafire had a much better rate of climb but the Wildcat was steady and gained speed faster in a steep dive. It was surprising to find that the Wildcat with its stubby little wings could sustain a steep turn inside the Seafire and this was all the more surprising and gratifying too bearing in mind that Bruce was by far the better pilot.

Adlam came out of the experience with renewed confidence in his Martlet, largely because he felt the "0.5 calibre shells from six Browning machine guns" (Thus narrowing the Martlet down to a Mk II, III or IV) would present him with a key advantage over the Seafire IIC

After the war, test pilot Captain Eric Brown went through his copious testing notes and called upon his experience to write succinct summaries and comparisons of the capabilities of every aircraft he had encountered in his book "Duels in the Sky". Several of his verdicts can be found for the variants listed below. But here is his assessment of the F4F-4 versus the Sea Hurricane IIC:

Here were two fighters almost evenly matched in combat performance and firepower, with the British fighter holding the edge. The Hurricane could exploit its superior rate of roll, the Wildcat its steeper angle of climb. In a dogfight the Hurricane could outturn the Wildcat, and it could evade a stern attack by half rolling and using its superior acceleration in a dive.

Verdict: This is a combat I have fought a few times in mock trials. The Hurricane could usually get in more camera gunshots than the Wildcat, but for neither was this an easy job. The Hurricane would probably have been more vulnerable to gun strikes than the Wildcat.

Variants

“The first ones arrived and the CO, Lieutenant Commander John Wintour, rushed off to collect the first one to be assembled. We were all sitting in the squadron office, not an aeroplane amongst us, when we heard a loud whining scream in the air. The whine turned into a thunderclap overhead. We rushed to the window and saw the splendid machine screeching uphill. She was blunt- nosed, square-tipped, and looked like an angry bee. When we came to try her for ourselves she turned out to be a tough, fiery, beautiful little aeroplane. There was a very fierce swing on take-off and landing which needed some handling. And the machines we got had been built for other European countries. Mine had a French accent and her oil pressure was in kilos. Then they were modified and given higher tail wheels, which brought the rudder into the slipstream and cured the swing.”

ADM 1/11207

To CinC Home Fleet 6/7/40

American types currently available: Grumman F3F-2; Brewster F2A-1

Both obsolescent. Grumman F4F is current type. 81 of these have been offered to this country.

This a/c was thoroughly inspected and flown in America by a most experienced FAA pilot, and was later seen in operation by a member of the Naval Staff who spent a week in the USS Saratoga last summer.

They concluded that, while it is a good aeroplane of its class, it is not designed to meet the far more stringent seagoing requirements of the FAA (which include wing-folding and navigability), and is inferior for shore based interceptor duty to current RAF types.

All USN fleet fighters are under-gunned.

As none fold, unsuitable for any but Furious.

For all other Fleet Fighter sqns, Fulmar is considered a better all around a/c than the American or RAF types because of its combination of heavy armament, first class navigability and communications, and long endurance. Its speed is adequate for attacking all contemporary German bombers and shadowers. It will go into all carriers.

Martlet Mk I

The French order for a modified export version of the early F4F-3 production run, the G-36A, had not been delivered by the time that country capitulated to the German Blitzkrieg.

Delivery was instead diverted to the Royal Navy where it would be named the Martlet Mk I.

The French had sought some refinements to the G-36 design: A reflector gunsight was fitted and, according to FAA Observer David Brown, some armour and fuel tank protection was installed in this variant. The USN would not get the reflector site on its Wildcats until 1941, nor armour until 1942.

Seven out of France's 91 production run had already been completed. These were retrofitted to RN standards, including switching out the French radio and throttle. The armament was also changed. The engine cowled guns were dropped and four .50cal (12.7mm) MG fitted in each wing.

The remainder would be completed to the RN's modified specification.

The first Martlet I was delivered to the FAA on July 27,1940, one month before the first F4F-3 was delivered to the US Navy.

Only 81 of the aircraft would reach the United Kingdom by the end of 1940. Ten would be lost when the cargo ship carrying them was sunk.

FAA pilot Henry 'Hank' Adlam wrote of his first encounter with the Martlet:

The reader may be surprised that the wheels had to be wound up and down manually by a handle at the lower right of the cockpit. This may sound difficult but the trick was to keep the flying speed down by climbing reasonably steeply away on take-off from the deck, thus with less wind resistance enabling the pilot to get the wheels up easily and quickly.

Captain Eric 'Winkle' Brown also noted some quirks with the fresh deliveries:

The Martlets we were equipped with had only a lap strap and no shoulder straps as safety harness, so each pilot was instructed to fly his aircraft to Croydon for the modification to full safety harness to be fitted.

Once they arrived, the FAA put the heavily hyped little fighter to the test.

FAA Observer David Brown stated in his book "Carrier Fighters":

The Royal Navy again found that the performance was lower than that claimed ... but the ability to reach 305mph at 15,000ft and about 285mph at sea level meant that its Martlet was the fastes fighter available until mid-1941.

Commander 'Mike' Crosley, who flew Hurricanes and Seafires, nevertheless encountered the Martlet and took a professional interest in its behaviour. As he states in "They Gave me a Seafire":

However, this early version had Wright Cyclone engines which were always overheating, seizing up or just stopping if hard pressed, for they were designed for civil aircraft. So only experienced pilots were allowed to fly them. They seemed to chuff around the circuit very fast indeed and the squadron pilots thought they were wonderful and far faster than a Hurricane. They were proud that they had been chosen to fly such a difficult aircraft, with its mass of mixture-control levers, its two-speed supercharger, its throttle which, someone said, opened the wrong way, its narrow, manually-raised undercarriage and its impressively large cockpit covered in dials, levers and switches.

Boscombe Down trials found the aircraft to be reasonable to fly and "free of vices". Its operational pilots, including Eric Brown, also put the Martlet through its paces.

The initial climb rate was one of the most sensational aspects of the performance of this little fighter. At 3300ft/min there was nothing around to touch it, and it was no slouch in level flight. Although we were to find that level speed was slower than that claimed, with top speed of 265 knots (491km/h) at 15,000ft (4570m) and about 248 knots (459km/h) at sea level, it was as good as the Hurricane Mk I and, in so far as we were aware at the time, the fastest fighter available for embarked operations. It was also a manoeuvrable aeroplane with a good rate of roll, but it needed plenty of stick handling on the part of the pilot to get the best out of it. By comparison with its British counterparts it was more stable to fly and therefore heavier to manoeuvre.

But there was criticism.

Opening the canopy in flight caused a violent draught, and there was no provision for jettisoning it in an emergency. Carbon monoxide was found in the cockpits. Also, the lack of automatic boost controls resulted in the pilot having to give extended and ongoing attention to the management of the engine during flight.

The little fighter also did not have the degree of pilot armour or the self-sealing fuel tanks combat experience had proven necessary for front-line aircraft. And converting the French gun mounts to carry the .50 calibre guns did not prove entirely successful and caused problems for the Mark I's entire service life.

As a result, these early Martlets were at best consigned to base defence squadrons and never saw service aboard an RN carrier in roles other than trainers. Most were used for performance trials, deck landing familiarisation and personal communications aircraft. As improved types became available, the Mark 1 was reallocated to training squadrons.

But the development potential of the type of was of great excitement to the pilots who got to fly them, such as Eric Brown:

Faults the Grumman fighter may well have had, but for me, in November 1940, it was a case of love at first sight; the Martlet was one of those few aircraft that I have encountered over the years with which I have instinctively felt rapport.

The first 12 aircraft were assigned to 804 Squadron based at Royal Naval Air Station Hatston in the Orkney Islands in September 1940. It was this squadron which scored the first shoot-down in an American-built aircraft: Two Martlet I’s combined to destroy a Ju88 near the Scapa Flow fleet naval base in the Orkney Islands.

One of this bomber's propellers was sent to Grumman as a trophy.

Operational max speed 492km/h at 4572m. Range 1884km

“The first features I noticed with the Wildcat II were an improvement in forward view, resulting from a smaller diameter, the more tapered cowling of the Twin Wasp, and its purr, quieter than that of the Cyclone.”

ADM 1/11980

AVA to PM 18/11/41

re Grummans your minute M.798?/1 of 16/8/41 and comments on mine 21/8/41

As you know, 5th Sea Lord has been over to US.

...He had expected to find good progress with the folding wing Grumman when he arrived, but on this point suffered heavy disappointment.

The position was made more difficult by the fact that the USN, having gained knowledge of how we were proposing to develop the use of the Grumman fighter, have also decided to adopt that machine for their own carriers.

Nevertheless, we were able to make arrangements with Adm Towers in Washington that the USN should release from allocations to their own Fleet, 29 planes for mounting in Illustrious and Formidable.

It is also clear from our experience in the Med that we require a replacement at the rate of not less than 12 planes per month when the carriers are operating...

Martlet Mk II

As the first of the French G-36As began to arrive on the British Islands, the Royal Navy ordered a further 100 Grumman G-36B variants under the designation “Martlet Mk II”.

These were to be built with the R-1830-90 single-stage, two-speed supercharged engine – making them essentially export versions of the F3F-3A. These did not have folding wings, but they came with two .50cal MG’s in each wing.

Then the order of this 100 machines was delayed: When the Royal Navy learned Grumman was working on its request for a folding-wing version of the F4F, it decided the benefits of waiting an extra six months for the delivery of this key feature outweighed the risks involved.

Weight was to prove a problem. The Martlet II would result to be somewhat underpowered.

Captain Brown would write:

The Martlet MkII had been tested at Boscombe Down where it had been found to weigh about 1000lb (454kg) heavier than the Mk I, but then, apart from the somewhat heavier Twin Wasp engine, it had wing-folding, with the inevitable weight penalty that such imposed, and toted an extra pair of 0.5in Colt-Browning M-2s. Understandably, this extra weight had some affect on performance and Boscombe Down testing revealed a maximum speed in MS gear of 254 knots (471 km/h) TAS as 5400ft (1647m) and the same speed in FS gear at 13,000ft (3965m), a range of 773nm (1432km) being achieved at 15,000ft (4574m) cruising at 143 knots (265km/h) IAS at full throttle in weak mixture and MS gear.

The first delivery of nine aircraft – which had had to have their folding wings retro-fitted - arrived in Britain in March 1941. Like the Mk I, the early Mk IIs mostly equipped FAA deck landing training squadrons, fighter training units and base defence squadrons.

However, 802 Squadron deployed with six non-folding Mk IIs to the escort carrier HMS Audacity in July 1941. The purpose was to serve in what was essentially a “proof of concept” mission in September of that year - the first active deployment of the escort carrier class of ship.

Three FW 200 Condors were destroyed by the Martlets and several submarine warnings issued. But one Martlet II was lost, along with its pilot Squadron Commander Lt Cdr John Wintour.

Another detachment of Martlet IIs went to sea aboard Audacity in December. While two Fw 200 Condors were claimed, the escort carrier was sunk by torpedo on December 20.

The Martlet II was actively deployed on RN fleet carriers including HMS Formidable and Illustrious in May 1942. These took part in operations around Madagascar.

Operational max speed: 472km/h at 2962m. Range 1432km

Captain Eric 'Winkle' Brown's combat assessment, as found in 'Duels in the Sky':

Wildcat II Versus Messerschmitt 109F: The Wildcat, although faster and more maneuverable than the Sea Hurricane, was still some 60mph slower than the German fighter. The lower the altitude the less the odds favored the Me109F. The Wildcat also had a heavier punch to deliver.

Verdict: As a dogfighter the Wildcat was superior to the Me109F, but the initiative always lay with the German because of superior performance. At low altitudes the Me109F had the edge over the Wildcat, but not by much.

Wildcat II Versus Junkers 88A-4: The odds in such a combat would be pretty evenly balanced. The Wildcat had a speed advantage, but defensively the Ju88 was well armed. The most effective attack would be head on to the German aircraft, a flat trajectory would prevent his dorsal gun from being brought to bear. The Wildcat would have to break off with a tight 180-degree diving turn to regain position for another head-on or beam attack.

Verdict: In single combat the Ju88 would be a tough opponent to overcome, but its greenhouse cockpit made the crew vulnerable to a well executed head-on attack by the Wildcat.

Martlet Mk III

The USN held doubts as to the reliability of supply of two-stage supercharged engines for the F4F-3’s entire production run. So they ordered a 95 machine run of a slightly lower powered variant, the F4F-3A, to be produced with the Pratt & Whitney R-1830-90 Twin Wasp 12-cylinder engine. This had a single-stage, two-speed supercharger. It promised enhanced performance at higher altitudes.

Greece, realising war was approaching their doorstep, placed an urgent order for this Wildcat. Thier production run had non-folding wings with four .50 cal MG.

The delivery order from Greece was signed on May 8, 1940. The first 30 F4F-3A machines completed would be diverted to fill this order.

The bulk of these aircraft were aboard cargo ships on their way to Greece when that nation and assisting British Expeditionary Forces capitulated to advancing German troops in April 1941. This cargo, once it had arrived at Port Suez, Egypt, was diverted to the Royal Navy.

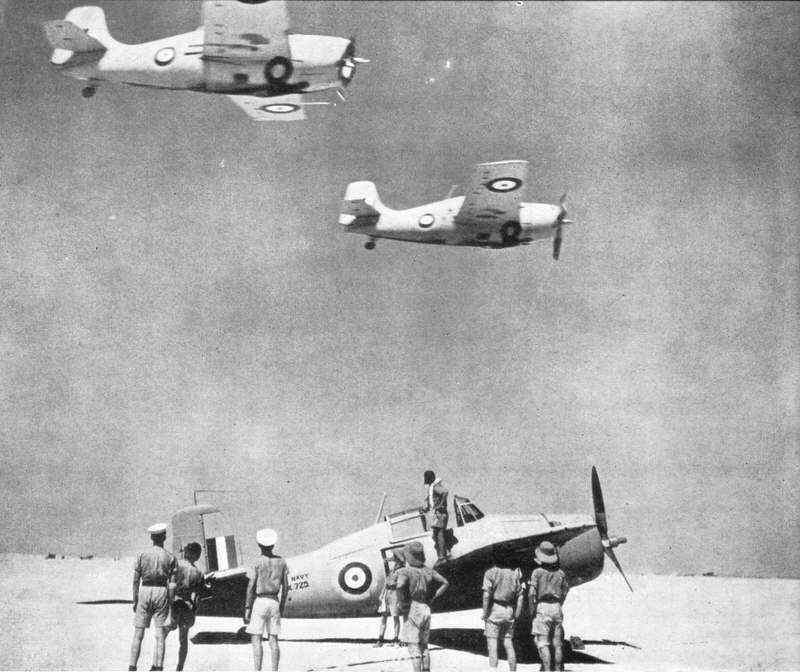

As these aircraft were already in the Mediterranean, they served with 805 and 806 Squadrons in Egypt’s Western Desert in ground attack and escort roles. A third unit, 795 Squadron, used Martlet IIIs in the training role while based in Kenya.

One Italian G.50 fighter and four bombers were claimed downed in late 1941 and 1942.

Operational max speed: 502km/h at 4877m. Range 1328km

Martlet Mk IV

The F4F-4B was among the first aircraft to be handed over to Great Britain under the 1941 Lend-Lease Act.

The 220 Wright Cyclone R-1820-40B single-stage, two-speed supercharger Martlets were designated Mk IV. It also had the heavy three-gun per folding wing arrangement as US F4F-4s.

Weight was again an issue.

Captain Brown:

The adverse effects of this weight escalation had occasioned no little concern, the deterioration in take-off distance and landing speed being viewed as particularly unfortunate, sine the greatest future value of the Grumman fighter was seen as its potential service aboard escort carriers with their regrettably short flight decks. As a consequence, in 1942, Grumman made a concerted effort to evolve a lighter version of the F4F tailored for the smaller carriers…

All 220 were delivered to the UK by November 1942. The first major operation in which the type took part was Operation TORCH, the joint US/UK assault on French North Africa. HMS Victorious carried 882 squadron, while HMS Formidable operated 893 squadron.

The Martlet IV also served aboard “USS Robin” (HMS Victorious) when she was ‘seconded’ to the US Pacific Fleet to operate alongside USS Saratoga in the Coral Sea and Solomon Islands between May and July of 1943.

Testing of the Mk IV was conducted by the Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment at Boscome Down in August 1943. It found the following figures with the production machine they were operating:

Climb rate:

6.6 minutes to 10,000ft

14.6 minutes to 20,000ft

29.1 minutes to 28,000ft

Maximum level speed

278mph at 3400ft

298mph at 14600ft

Operational max speed: 480km/h at 4267m

Captain Eric 'Winkle' Brown's combat assessment, as found in 'Duels in the Sky':

Wildcat IV Versus Focke-Wulf 19A-4 and A-4/U8: The only superiority that could be claimed by the Wildcat was its ability to outturn the German fighter, but turning doesn't win battles. In every other department the Fw 190 was in command. Even in the fighter-bomber role the German faced minimal danger, and he could always jettison his bombs in an emergency to defend himself.

Verdict: The superiority of the Fw 190A-4 and A-4/U8 was so comprehensive that the Wildcat had little or no chance to do anything more than perhaps harry the German enough to make him jettison his bombs prematurely.

Wildcat Mk V

The FM-1 General Motors’ Eastern Aircraft Division licence-built version of the Wildcat also saw service with the RN. Some 311 of these were transferred to the UK under lend-lease provisions.

Originally designated Martlet V, a January 1944 decision to end the confusion of differing names for the same fighter saw it redesignated Wildcat Mk V.

As with the US FM-1s, the RN was to use this late-model Wildcat aboard escort carriers as larger, higher performance fighters were now available for the fleet carriers.

FAA pilot Henry 'Hank' Adlam had this to say about the Wildcat in his book, "On and Off the Flight Deck":

This is where the Wildcats, on combat patrol as a pair could come in fast on call-up from the Swordfish to fire at the enemy gun crews on the deck of the U-Boat who, intent on returning fire against the Wildcats, enabled the Swordfish to continue their depth charge attack. The Wildcat was slightly slower at that time than other fighter aircraft but it had a formidable fire-power of six 0.5 Browning machine guns and was eminently suitable for this situation.

The Mk V had had its gun armament reduced to a total of four .50cal MG in an effort to save weight and boost ammunition loads. It also had the same 1200hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830-86 two-stage, two-speed supercharger as the USN FM-1.

The type began to arrive in the UK in late 1943 but was not to see action until February 1944 aboard HMS Pursuer on convoy escort duty.

Operational max speed: 512km/h at 5913m

Wildcat Mk VI (FM-2)

This was the final version of the Wildcat to see service with the Fleet Air Arm. The 340 machines delivered in late 1944 and early 1945 were essentially the same as the USN’s FM-2.

Captain Brown was impressed:

The FM-2 alias Wildcat Mk VI was, from some aspects, the most satisfactory of all versions of the little Grumman fighter to fly, some of the early faults that had persisted having been finally rectified. For example, this model could be spun without impunity whereas the spinning of its predecessors was not permitted an in the event of an inadvertent spin a great deal of muscle power had to be exerted to get the control column forward, the recovery characteristics being somewhat short of pleasant.

This model had a 1350hp Wright R-1820-56 nine-cylinder, air-cooled, radial engine. It carried the by now standard four .50cal MGs and was plumbed for a 58gal (220litre) drop tank or 250lb (113kg) bomb under each wing.

Once again the type was destined for the growing number of escort carriers protecting convoys and supporting fleet operations in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans.

Many were too small for the new F6F Hellcat, which needed a significantly greater take-off run than the Wildcat. Therefore the type's ongoing operation was assured - at least for the time being.

This model took part in the FAA’s last Wildcat combat: In the final week of the European war HMS Searcher’s 882 Squadron tangled with eight Messerschmitt BF109G fighters off the Norwegian coast. Four 109s were claimed downed in the action.

Operational max speed: 505km/h at 4039m

Captain Eric 'Winkle' Brown's combat assessment, as found in 'Duels in the Sky':

Wildcat VI Versus Messerschmitt 109G-6: The agile little Wildcat could outmaneuver the latest version of the Me 109, but the performance differential had widened and the German could run rings around the Wildcat. If the Me 109G-6 was tempted to mix it in a dogfight, the Wildcat had a better than even chance of success.

Verdict: The Wildcat was no real match for the Me 109G-6, but the German could not afford to take liberties with his angry little opponent.

Wildcat VI Versus Focke-Wulf A-4: The formidable Fw 190 held all the advantages in this contest, and there was really no way out of the dilemma for the Wildcat. Even in a turning circle it could not evade the German fighter for the first 120 degrees, and that was more than enough time for the powerful armament of the Fw 190 to take effect.

Verdict: The Wildcat had little chance of surviving single combat with the Fw 190. Its only hope lay in overwhelming the German by force of numbers.

“Leaving aside my emotional affection for the first of the Grumman shipboard fighter monoplanes, I would still assess the Wilcdat as the outstanding naval fighter of the early years of WWII. Its ruggedness meant that it had a much lower attrition rate on carrier operations than, say, the Sea Hurricane or the Seafire, and although it had neither the performance nor the aesthetic appeal of the latter, it was the perfect compromise solution designed specifically for the naval environment, to such a degree indeed that it was easier to take-off or land on an aircraft carrier than on a runway, where it was inclined to be fickle about the direction it took up. With its excellent patrol range – I actually flew one sortie of four-and-a-half hours in this fighter – and fine ditching characteristics, for which I can vouch as a matter of personal experience, this Grumman fighter was, for my money, one of the finest shipboard aeroplanes ever created.”